The Short Version:

What if there was a magic model to become rich and powerful. That anybody could use – without any talent. What if this model could make you one of the richest and most powerful people in the history of Hollywood (with no acting, directing, writing or producing talent)? What if you could use the exact model to facilitate the hottest and biggest investment banking deal of the time (with no experience as an investment banker)? And then use the model to conquer Madison Avenue to make one of the most memorable campaigns for Coca Cola? What if you could just use the same model over and over again on whatever took your interest, and have unprecented success?

This post will show you exactly how to do it. Well, at least, how one guy exactly did it.

MICHAEL OVITZ

I was introduced to the absolute magic of Michael Ovitz’s business model from a book called The Art of Profitability by Adrian Slywotsky. I loved the concept, so bought his prescribed book Power to Burn by Stephen Singular which chronicled Ovitz and his company Creative Artists Agency (CAA) in the 1980s and 1990s.

THE MODEL

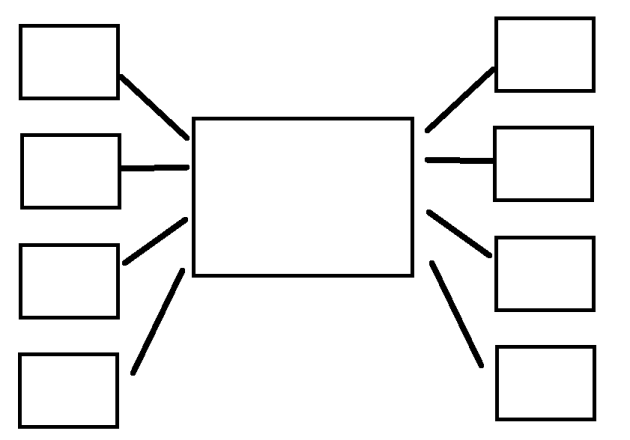

Slywotsky uses Michael Ovitz’s CAA agency model to describe “Switchboard Profit” model:

Sellers: Actors, Writers, Producers, Directors

Middle: Micahel Ovitz (Agency)

Buyers: TV Studios

Switchboard profit is to act as an intermediary between buyers and sellers. A match-making service. Think any kind of agency – real estate, recruitment, sports agents, even investment banking.

“TV Packaging” was when an agency packaged a group of actors, writers, producers and directors to sell a new show to a studio. Most TV you saw from the 1960s on was done this way.

So what was so special about Ovitz?

Ovitz took the model for TV packaging and applied it to movies – never done before successfully.

Then he applied this to Investment Banking: He sold the media company MCA/Universal to Matsushita, a job usually pinned for investment banks – and collected bankers’ fees along the way. And successfully annoyed investment banks.

Then he applied this logic to become a sports agent. Then to TV Commercials.

But how did he gather such momentum? How did he keep the supply?

CUSTOMER KNOWLEDGE

Before each meeting with a potential client to sign up, Ovitz researched the target heavily. He knew the background of each actor, director, writer – everything they had accomplished. He even applied this when he was trying to win the design of famed architect I. M. Pei for his LA Headquarters – and won it despite Pei’s complete reluctance to take a project like that on.

He knew all the gripes, the insecurities, the anxieties that his customer segment had. Actors are always worried about their next job – where was it going to come from? Ovitz built confidence that he would take on the “work” pipeline, and they just had to concentrate on what their art – the acting. How did he do this? Like this:

THE RIGHT HELP FROM THE RIGHT PEOPLE

His transition from the model from TV to Movies wouldn’t be easy. He signed up veteran of the film industry Marty Baum and made him a partner at CAA. When he was building the model for movie packaging, he probed Marty constantly. What are the fears and insecurities of stars, directors and producers? What makes a good script? Where did the money come from to make a movie?

GOAL EXECUTION

Ovitz kept clear goals and ruthlessly executed them. He redefined goals month by month.

ABC – ALWAYS BE COMMUNICATING

Ovitz was not always doing deals. He called around town constantly to find out which business manager and lawyers were representing which actors and directors. He was not always selling. He found out which networks and studio executives were looking for work and asked if he could help them find employment now or in the future.

SIGNED THE RIGHT CLIENTS

Ovitz knew that the model required the right clients and quickly learned that signing literary agent Morton Janklow would be key to sell TV packages to networks (it was…)

TALKED A BIG GAME

He acted like he owned the place and exuded confidence, even when the agency was nothing. When courting the literary agent Janklow, he told them that his agency was going to be the biggest in the world, despite the fact that at the time they were barely even a company. Despite getting laughed at, he got their attention.

STOPPED AT NOTHING

Despite Janklow’s lack of enthusiasm, he persisted by calling again and again. He flew to New York to get half hour of the agency’s time, and literally put the watch on the manager’s desk. He then said he’d call twice a week asking for a manuscript.

STEALTH

It’s hard to imagine in current days of endless self-promotion via Linkedin posts, podcasts and interviews that someone would opt to take a quiet profile. Ovitz was obsessed with keeping himself out of the spotlight. Why? He didn’t want to reveal his strategy, his secrets. Though continually pestered for interviews, he refused most of them – he even refused Stephen Singular’s request to help write the book for a while.

There’s no credible quick way to riches in busines. But before you start anything, the first thing you should do is look at your “profit model”. This is not the business model – it goes way beyond this.